Everyone

knows about Milgrams famous experiment. At least the patients I can hear from

my office discussing it do. In case you don’t know it, here’s a short summary:

Milgram has tested in the 60th of the last century how willing his participants (ordinary people without any special interest in harming others) were to follow orders from an authority (the experimenter) even if they had to put another person in danger for that.

In his experiments the participant was given the role of a teacher whose task was to give electrical shocks to a learner whenever the learner did a mistake in a word-paring task. The learner was a conferderate and not really harmed by the electrical shocks. However the subject didn’t know this: he was given a trial-shock himself before the experiment in order to make the electrical-stimulator more believable and then placed in a separate room than the learner.

In Milgrams first experiment 65% of participants continued until the final voltage of 450 V, even though they probably believed the learner was in danger(1, 2): The stimulator was labeled with “Danger: Serve Shock” at 375 Volt (and the four steps following that) and only with “XXX” at 435V and 450V. Furthermore the (supposed) learner pounded against the wall at 300V and 315V and is not heard afterwards, i.e. he doesn’t answer anymore.

This experiment has been repeated several times by Milgram himself and others under slightly different conditions to find out which factors lead to obedience. However, in all the experiments a high proportion of participants “cooperated” until the final shock, despite experiencing high stress while doing so. (2)

Today, it is said, ethic committees would not allow this study anymore, precisely because of the high stress that was inflicted on the participants.

However, I wonder, what differentiates “modern” studies from that of Milgrams. Participants are still stressed and potentially harmed. I’m thinking about PTSD-studies where participants suffering from post-traumatic-stress-disorder are shown pictures related to their trauma, stress-studies where participants are stressed as much as possible in order to investigate the biological and psychological responses to stressors in healthy participants as well as in participants suffering from various disorders, pain-studies where the conditions which lead to more or less subjective pain or the pain-inhibitory system(s) is/are examined, conditioning-studies which involve learned helplessness and so on…

Now obviously the potential harm that is done to the participants is weighted against potential benefits of the study: the goal of such studies is to find mechanisms that make people more vulnerable to disorders or those that would potentially lead to the development of new treatments: after all, something has to be learned about disorders or suffering in general in order to understand and reduce it.

But, I don’t know…

Milgram explains (as one of 13 potential contributing factors for the obedience of his subjects) that “the experiment is, on the face of it, designed to attain a worthy purpose – advancement of knowledge about learning and memory. Obedience occurs not as an end in itself, but as an instrumental element in a situation that the subject construes as significant, and meaningful. He may not be able to see its full significance, but he may properly assume that the experimenter does.” (3)

All experiments should be designed to “[A]ttain a worth purpose – advancement of knowledge”, aren’t they? I think it would be bad if they weren’t (4)… but are they also significant in meaning?

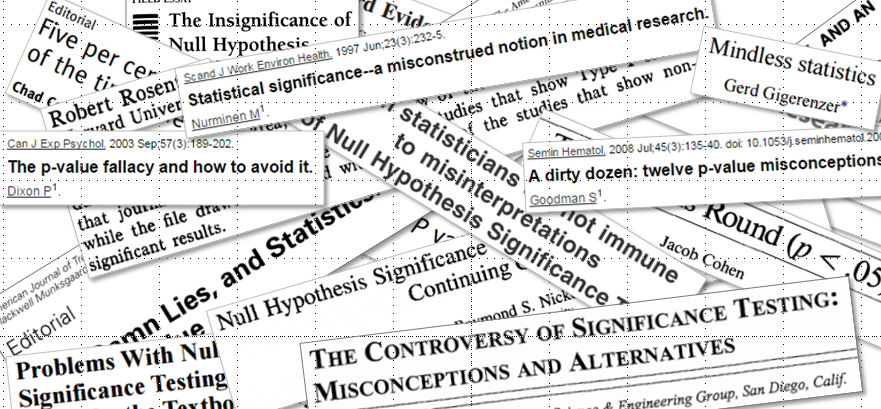

I think, a study of which we don’t have any clue whether or not the reported results are (likely) true or not can’t be meaningful. (5)

Reproducibility in psychology is low (6) and most neuroscientific studies are underpowered (7). Ioannidis (8) famous paper shows that “most published research findings [in biomedical research] are false.” Negative findings remain often unpublished.

Yet, for all the p-hacked and unreproduceable studies a lot of resources were used (or wasted): Money that could have been spend otherwise, as well as time and effort of the participants and the people conducting, writing, publishing and reading the study.

And maybe worse than that, some subjects suffer under the study – like the fake subjects (the learners) in Milgrams study did: they are given electrical shocks, shown awful pictures, brought into situations they fear or reminded on their worst times.

Is this right? If there were true meaning, such experiments might be justified. The subjects sign a consent form and they know they are free to leave any time. But just like the real subjects (the teachers) in Milgrams studies, they usually don’t leave because they think they are helping science advance and develop new treatments. They don’t know about statistical problems, p-hacking and the pressure to publish anything out of a pile of underpowered noise. They don’t know the study they are participating in might be meaningless.

But I do. (9) I have tortured participants knowing the experiment is worthless. I will probably do similar things again. New study new hunt for statistical significances on the cost of participants. This is very false.

I don’t know what to do about it, I really don’t.

Since not every study involves mental of physical pain for the subjects, I could concentrate on such studies or search for another job. But while that might allow me more sleep at night (likely not) it wouldn’t solve the problem (10). After all the studies are not stressful/painful/frightening for the participants because we want to torture them, but because it is seen as necessary for the “advancement of knowledge” about these states (11).

Therefore what remains is that studies should have sufficient power and be carefully designed to detect effects when present and to avoid unnecessary harm. Everybody agrees with that, yet it is not done.

As a PhD-student I'm not in the position to change that (and I don't know if anyone is). It is false to conduct worthless experiments, that (potentially) harm the participants and it is false to do nothing just to reduce own stress.

So what should I do?

click on image to enlarge

______________________________________________

(1) In an

interview after the experiment the subjects were asked what they think how

painful the last shocks where for the learner on 14-point scale from “not

painful at all” to “extremely painful” and the mean answer was 13.42. Milgram, S. (1963). Behavioral Study of Obedience. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67(4). [PDF-link] (see page 5 of pdf / page 375)

(2) Furthermore,

according to Milgrams description many subjects were extremely nervous upon administering

the high electrical shocks. They “sweat, tremble, stutter, bite their lips,

groan, and dig their finger-nails into their flesh.” Milgram, S. (1963). Behavioral Study of Obedience. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67(4). [PDF-link] (see page 5 of pdf / page 375)

(3) Milgram

writes that here: Milgram, S. (1963). Behavioral Study of Obedience. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67(4). [PDF-link] (see page 7 of pdf / page 377, point 2)

See also:

Haslam SA, Reicher SD (2012) Contesting the “Nature” Of Conformity: What Milgram and Zimbardo's Studies Really Show. PLoS Biol 10(11): e1001426. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001426 [PDF-link] (page 3)

“However, some of the most compelling evidence that participants' administration of shocks results from their identification with Milgram's scientific goals comes from what happened after the study had ended. In his debriefing, Milgram praised participants for their commitment to the advancement of science, especially as it had come at the cost of personal discomfort. This inoculated them against doubts concerning their own punitive actions, but it also it led them to support more of such actions in the future. “I am happy to have been of service,” one typical participant responded, “Continue your experiments by all means as long as good can come of them. In this crazy mixed up world of ours, every bit of goodness is needed” (S. Haslam, SD Reicher, K Millward, R MacDonald, unpublished data). […] what is shocking about Milgram's experiments is that rather than being distressed by their actions, participants could be led to construe them as “service” in the cause of “goodness.” […]”

(4) Which of course is possible: A goal of scientific experiments can also be to have something to publish or to “show” that one is right (even if that is not clear).

Haslam SA, Reicher SD (2012) Contesting the “Nature” Of Conformity: What Milgram and Zimbardo's Studies Really Show. PLoS Biol 10(11): e1001426. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001426 [PDF-link] (page 3)

“However, some of the most compelling evidence that participants' administration of shocks results from their identification with Milgram's scientific goals comes from what happened after the study had ended. In his debriefing, Milgram praised participants for their commitment to the advancement of science, especially as it had come at the cost of personal discomfort. This inoculated them against doubts concerning their own punitive actions, but it also it led them to support more of such actions in the future. “I am happy to have been of service,” one typical participant responded, “Continue your experiments by all means as long as good can come of them. In this crazy mixed up world of ours, every bit of goodness is needed” (S. Haslam, SD Reicher, K Millward, R MacDonald, unpublished data). […] what is shocking about Milgram's experiments is that rather than being distressed by their actions, participants could be led to construe them as “service” in the cause of “goodness.” […]”

(4) Which of course is possible: A goal of scientific experiments can also be to have something to publish or to “show” that one is right (even if that is not clear).

(5) The reasoning behind a study can still be meaningful of course. E.g. if a treatment were tested, that might be meaningful. But any study which tests it with getting a true result at or below chance-level isn’t imo.

Summary/comment

here: Baker, M. (2015). Over half of psychology studies fail reproducibility test. Nature News. doi:10.1038/nature.2015.18248

(7) Button, K. et al. (2013). Power failure: Why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 14, 365-376. doi:10.1038/nrn3475

(9) And others know too. I just don’t want to speak for other people, because I don’t know what they really think.

(10) That’s what horrible persons always say, right? But I don't know whats right.

(11) It would of course still be possible to invite participants that feel stressed at the moment to the lab when they experience that emotion. But obviously this has clear disadvantages since there were much more confounding variables then. Probably the disadvantages are so big that this would do even more harm, when it can be done otherwise. But I don’t know. In some/lots of instances this is of course the only possibility anyways. In others I don’t know if it would make any sense at all. That would then be a total waste as well.

Also interesting:

Blass, T. (1999). The Milgram Paradigm After 35 Years: Some Things We Now Know About Obedience to Authority. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 29(5), 955-978. [PDF-link]

Milgram, S. (1974). Obedience to authority: An experimental view. New York: Harper & Row. [PDF-link]